Our history

Built in 1587, The Rose was the fifth purpose-built open-air theatre in London, and the first on Bankside.

It stood on the south side of the Thames, in the Liberty of the Clink in Southwark, on land relatively recently reclaimed from the river.

This was an area already rich in other leisure attractions such as taverns, brothels, gaming dens, bowling alleys, and bull and bear baiting arenas.

To learn more about its history, read on…

Detail of John Norden's 1593 Map of London, showing The Rose Playhouse on Bankside.

Another circular building, ‘The Bear House’ or bear-baiting arena, is just to the north-west of it.

1587: Beginning – phase 1

The Rose was built by Philip Henslowe, a shrewd local businessman and property developer.

In 1585, when he was about 35 years old, he leased part of a garden plot on Bankside called The Little Rose, and then commissioned John Griggs, a carpenter, to construct a new playhouse on the site. It opened for business in 1587.

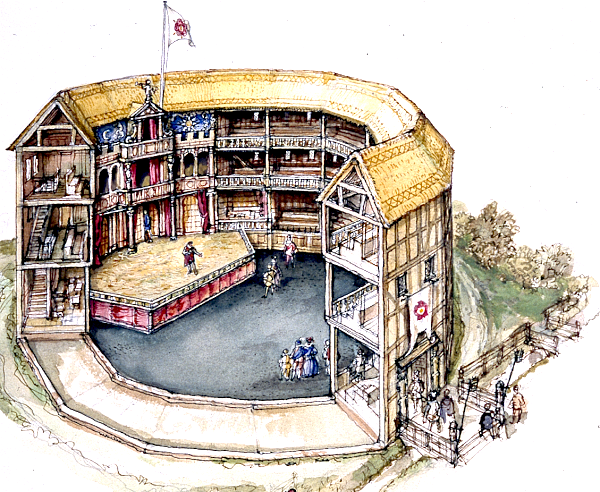

The original Rose Playhouse

by C. Walter Hodges

Its original shape was a circular 14-sided polygon, approximately 72 feet (22 metres) in diameter.

It was framed in wood, with three tiers of seated galleries covered by a thatched roof, which surrounded an open yard that sloped downwards at a 5° angle towards a shallow trapezoid-shaped stage that projected into the yard from the northern side of the inner wall.

Because the stage likely had no roof, there was probably no need for any supporting pillars, leaving sight-lines from the yard and galleries entirely clear.

The audience entered the playhouse from Maiden Lane (now called Park Street), crossing over a shallow ditch that ran along the south-side of the property, and paying a penny to enter the yard to stand as groundlings, or more to enter into and sit in the galleries.

1591-2: Expansion – phase 2

The Rose was clearly a success and must have been playing to packed houses, because in 1591-92 Henslowe decided to invest more money in having the playhouse expanded in order to increase audience capacity.

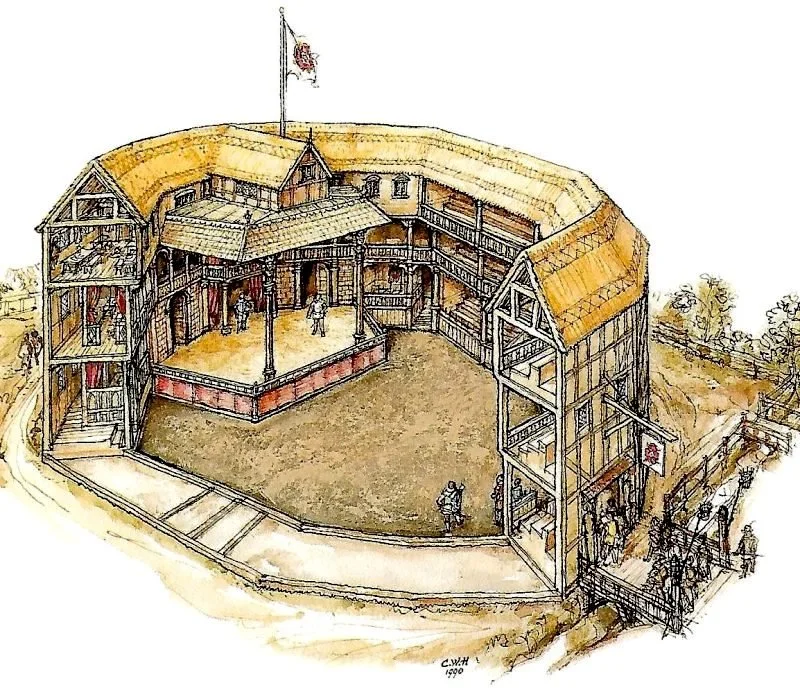

The expanded Rose Playhouse

by C. Walter Hodges

The bays on the northern side were pushed further north and widened out east-west, creating a flattened oval-shape. This allowed the stage to be set further back by six and a half feet (two metres), and stage-posts were added to support a roof covering it.

Relatively little of The Rose’s history was recorded until this time, when, in 1592, Henslowe began keeping an accounts book – now commonly called his Diary.

This was also the year that Henslowe’s step-daughter married the eminent actor, Edward Alleyn. From then on, Alleyn was closely associated with The Rose and its fortunes.

Edward Alleyn (1626), and his wife Joan (1596)

artists unknown

Dulwich Picture Gallery

Henslowe’s Diary

In 1619, after his retirement from acting, Alleyn founded the College of God’s Gift (now Dulwich College), where many of Henslowe’s papers have survived, including his Diary – the single most important document about the theatre of his time.

The Diary details his spending on the theatre building from 1592. There are expenditure records for props and costumes, and payments to dramatists for the commissioning of plays.

Henslowe’s ‘Diary’ or account book

Dulwich College Archives

It also records Henslowe’s income from the playhouse. It lists hundreds of performances of the plays that were staged there along with the money he received for each one, and provides an extraordinarily detailed insight into the repertoire of The Rose, the tastes of its audiences, and the performance practices of the playing companies who acted there.

It is from these records that we know The Rose was home to plays by most of the leading dramatists of the Elizabethan age, including Christopher Marlowe, Thomas Kyd, and William Shakespeare, and was the launching ground for the new generation of playwrights who emerged from the mid-1590s onwards, like Thomas Dekker, Thomas Heywood, George Chapman, and Ben Jonson, who together would go on to dominate the London stage for the next twenty years.

The Dulwich papers constitute a uniquely rich resource for the study of the Elizabethan stage, enabling us to establish the history of The Rose in far greater detail than for any other playhouse of the time.

1600-5: Final years and closure

The Rose’s success soon encouraged other playhouses to be built on Bankside – The Swan in 1595, and then The Globe in 1599.

The following year, in January 1600, Henslowe and Alleyn commissioned Peter Street – the same carpenter who had just built The Globe – to construct a new playhouse north of the river in Clerkenwell. They called their new venue The Fortune, and the Admiral’s Men, who had been in residence at The Rose since 1594, moved in.

Writing to the City of London authorities in support of the building of the new playhouse, the Admiral’s Men’s patron, The Earl of Nottingham, had described The Rose as being in a state of “dangerous decay”, but Henslowe’s records show that he continued to rent it out to other playing companies. Pembroke’s Men acted at The Rose in the autumn of 1600, and Worcester’s Men in the summer of 1602.

By 1603, however, The Rose appears to have fallen out of use, when a rapid sequence of events saw all public performances in London suspended – first for the illness, death, and burial of Queen Elizabeth, then for the arrival into the capital of the new King, James I, and then for another outbreak of plague.

When playhouses were finally allowed to reopen again the following year, in 1604, The Rose was not named on the list of permitted venues. Henslowe had attempted to extend the lease of the land it was built on in 1603, but facing a tripling of the rent he instead allowed it to expire in September 1605, and so either before or shortly after this The Rose was very probably demolished and its timbers taken away for reuse elsewhere.

Soon it vanished from the map altogether…

To learn about the rediscovery of the remains of the Rose in 1989, continue here: